(written for and rejected by an online travel site—too long—back in late 90’s.)

Rural California seemed to start with Goleta in the rearview mirror. Driving north out of Santa Barbara on Highway 101, there is a long, gorgeous stretch between mountains and shore, where the elongated Santa Barbara plain is reduced to just a sliver of farmland and undeveloped beach. Eventually it is too narrow even for the fields, and civilization just tapers off into nothingness. Just the road, sea and mountains.

The last vestige of the plain comes to an abrupt end at Gaviota, where the 101 makes a veer to the true north from its western course along the South Coast. A winding pass permits passage through the wall of the Santa Ynez mountains (one of those Transverse ranges, erupting when plates collide and causing so much seismic mischief in the LA Basin). To the burro riding padres of Father Serra’s world this must have seemed a more gradual—if more arduous—transition, but in a speeding car the change is sudden and stunning. The narrow walls of the defile reveal a whole other world of crags and dense oak forests. The mountains are stark, untamed; the slopes impenetrable. Signs warn of falling rocks and wild beasts. We sped up the long grade, at the top of which was a truck pullover, where a battered orange sign announced “Nojoqui Park”. Curiosity got the best of me and I veered off.

Once off the highway, we were plunged immediately into the primeval forest. An ancient, narrow road, cracked and sundered, twisted its way round slopes beneath the trees. The air was dark, almost creepy, penetrated only feebly by rays of sunlight. Birds flushed in all directions. We had the near instantaneous feeling of being lost, only minutes off the 101. Round we wound, down and down, till at last we were dumped into a sparkling green valley. We parked along side a rotting wooden fence to stretch our legs and snap some pictures. Birds called from all directions and a rabbit darted at our feet. We walked about a bit, listening and watching. We were completely on our own in this tiny, beautiful valley. I had no idea where this Nojoqui Park—or even what—would be, but if it were anything as beautiful as this then we were in for a treat. Back in the car, my wife studied the county map and found Nojoqui Falls. Now our curiosity was truly piqued, and we followed the old road, which in a few minutes seemed to lead us right through a farm, past barn and aging machinery. A right turn eventually led us to the park. As if out of nowhere, there were crowds of people about, seemingly hundreds of them, and animals—cows, pigs, sheep and goats by the score. We had stumbled onto a gathering of the Buellton 4H club. Fortunately there was plenty of parking under the pines where the trail began. It was a very gradual uphill walk of perhaps three-quarters of a mile, alongside the gurgling stream, round trees and over rocks, some laid out stepwise. Squirrels chattered in the branches. The weather had turned cool, cloudy and was threatening rain, and in these coastal canyons you could still feel the dampness of the morning’s fog.

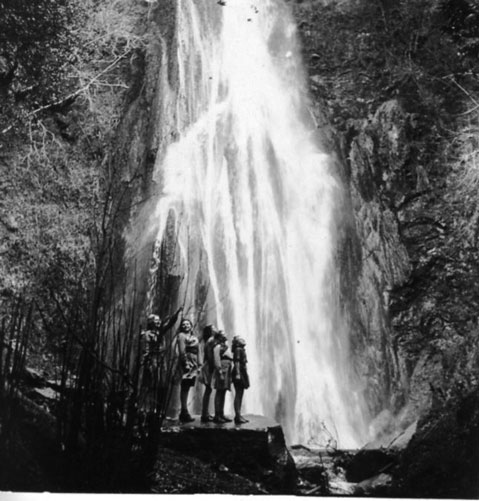

Suddenly, the narrow canyon opened up and the sounds of the creek were swallowed in the rush of falling water. Ahead towered Nojoqui Falls. A good 80 feet in height, its grandeur was not in the volume of water tumbling over but the cathedral-like patterns of its fall. The rock upstream, it seems, is an easily soluble limestone while the falls themselves tumble over much harder granite. Over the eons evaporating mists have left their mineral mark and built up layers of limestone in the very shape of the Falls themselves, and then the water, in its turn erodes patterns anew and falls in the most perfectly graceful gestures. A perpetual motion machine of water and rock and air, Nojoqui Falls shall continue its slow, inexorable growth until the limestone that lines the stream above is eroded away completely. There was a bench and we sat and watched the water flow through its ancient etchings. It seemed such a shame that we had left the camera behind in the car. We had the binoculars, though, and through them observed flycatchers and bluebirds flitting in the branches above. I walked down to the pool and reached in elbow deep. The water was cold, clear. The footing slippery. We sat and watched and listened. The mist wafted into our faces. Who knows for how long people have come to this place tucked back in the mountains to watch and listen. Who knows what spiritual significance this place held for the local Chumash Indian civilization. Indeed, that such a splendid and rare natural phenomenon has remained but a county park is one of bureaucracy’s little mysteries—though Santa Barbara County has done an excellent job maintaining the site (and providing the geologic information on these very peculiar falls). The urge to remain just a little bit longer was powerful. But for us time was pressing. Places to go, reservations to keep. We tracked back to the car, slowly. The sound of falling water faded behind us. Squirrels rattled about in the trees and the sun was breaking through.

Back in the parking lot all was a bustle of competition. Walking past the car I wandered down to the 4H pens, where kids in their green ties and caps gently prodded their hogs around before the judges. Those reservations would hold a few minutes longer. I watched, applauding, and took in the sweet reek of pig.